Library of Congress photo

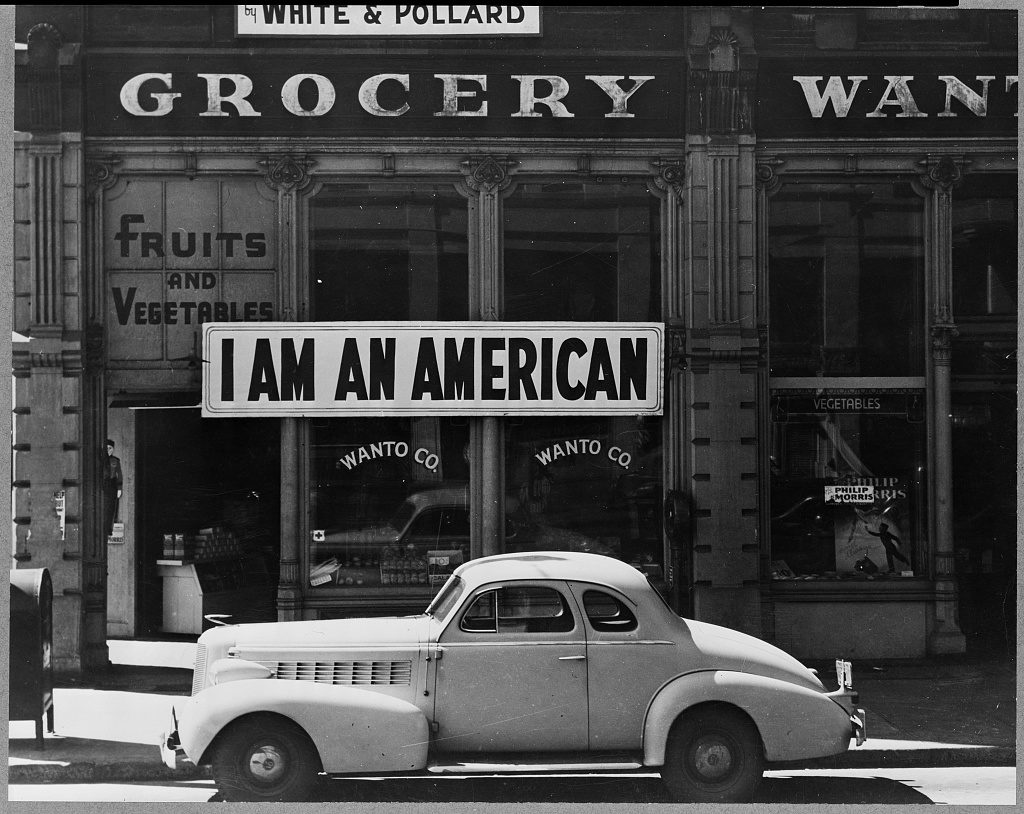

Years after I wrote the next piece I visited Manzanar, the former internment camp in the high desert east of the Sierra Nevada where the U.S. government interned Japanese-Americans. There was a museum that showed how the internees had been treated. It showed the anti-Japanese signs and racism, the rounding-up and processing, the tight quarters, lack of privacy, etc., all of which illustrates the Japanese American point of view. The museum also showed dances, baseball games, ceremonial rock gardens, etc., which makes the government’s point that these camps, while not good, were not Soviet or Nazi-style camps. What the museum did not show was the war news, the stories of atrocities in China and the Philippines, and alarmist journalism that prepared the whites of 1942 to demand the Japanese be interned.

Looking at that museum at Manzanar, a person might wonder: Why did the whites support this? Because they were racist to begin with? That is the modern answer, and there is a measure of truth to it. But much of the reason was the ugly war news from Asia and the hysteria spread by American newspapers. The newspapers of 1941 were often megaphones for the thoughts and feelings of whites who were angry and scared. The newspapers mostly did not talk to the Japanese Americans or those who supported them. In the years earlier, West Coast port authorities and ocean carriers had prevented an embargo on the sale of scrap steel to Japan because they had a voice. They had powerful friends. The Japanese Americans were voiceless and friendless. The government that was supposed to protect them identified them by race and put them in camps, with hardly a mention of the Constitution from anyone.

The next piece is a criticism of the press. I based it on research in the Seattle Times archives — not because I had any reason to target my employer, but because its archives were handy. I believe the Times was better than many newspapers in 1941, particularly the California papers — which, I think, makes my argument all the stronger.

I wrote the piece for Liberty, a libertarian and classical liberal magazine in Port Townsend. It ran in the April 2002 issue.

The decision to intern of the Japanese Americans, announced sixty years ago this month, is remembered today as a infamous attack on constitutional rights. Years afterward, the United States apologized for doing it, and paid an indemnity. But in 1942 it was hardly questioned.

This I discovered when I spent several lunch hours in front of microfilm reader, tracking the story in the Seattle Times. There is nothing better to get a flavor of a time than reading through a newspaper, particularly a mainstream, non-ideological paper like the Times was and is. It reflects the passions and prejudices of the day, even, perchance, when it tries not to.

At the beginning of 1942 Seattle’s afternoon newspaper was saturated with war, and had been for many months—the events of war, arguments about war, preparations for war. As 1942 opened, just three weeks after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Manila was falling to the Japanese army and MacArthur’s forces in the Philippines were retreating to the peninsula of Bataan. The Japanese were advancing down the Malay Peninsula toward Singapore. The Russians were counterattacking the Germans, who had been stopped in the suburbs of Moscow. Back in the States, the Roosevelt administration was proposing to double the income tax and to begin withholding for the first time; to control prices; to stop the production of cars and to ration gasoline and tires.

The year’s first story regarding enemy aliens was the order Jan. 1 by Attorney General Francis Biddle that German, Italian and Japanese nationals surrender their guns. I had heard the line, “The first thing they come after is your guns,” and doubted it, but then it was true. Axis nationals would also have to notify U.S. authorities of any plans to leave town. On Jan. 3 it was announced that travel permits would be issued at the U.S. Court House in Seattle.

It was all very civilized—except when it was not. On Jan. 5, a 20-year-old Seattle restaurant worker, a French Canadian, was slashed in the throat by a man who said, “I always wanted to get a Jap or an Italian.”

A few days later there was a little article about the 68 employees of the Union Electric Co., Seattle, who had formed a club in which each paid 10 cents for each Japanese plane shot down, with the money to buy war bonds. They it the “Slap-a-Jap Club.”

On Jan. 6, the Times offered a small editorial—not the main one—that expressed concern about all the firings of “aliens and citizens of foreign birth.” The editors appealed for “fair consideration in the case of each efficient worker and against indiscriminate and wholesale dismissals.” They reminded readers that “no one in this country is by many ages detached from foreign parentage.” And they summed up: “Let the FBI and all other authorities do the ferreting for danger. Help them with information whenever possible; but do not complicate the situation by spreading unwarranted prejudice.”

The position was: Let the authorities decide about aliens.

What of non-aliens? Two days later, two U.S.-born Japanese were arrested for subversion. Another small editorial said there was no reason to be prejudiced against “other Japanese, especially the large number of native-born, whose manifestations of American loyalty leave no room for suspicion.”

No room for suspicion, especially of the native-born. That was a position worth defending. But though the paper was sympathetic to the Japanese, and tried to cool the tempers of prejudice, it did not defend this position against the government. January 1942 was a time for unity, not obstruction. And the editorial voice was not the only voice in the paper. There were other voices in the news columns, reflecting the choices of news editors, the thoughts of reporters and the words of those who made news.

On Jan. 9 the paper reported a Japanese drug store proprietor, age 30, shot by a Negro man who “apparently bore some resentment.” It was not reported as a racial or political incident. Two days later the assailant was picked up, and said he had entered the store whistling “God Bless America,” heard a disparaging remark from the proprietor, and blasted him with his .38 revolver.

On Jan. 15 it was reported that 442 Americans captured on Guam had been interned on the Japanese island of Shikoku. On Jan. 17, a story from China: “Jap Massacre of U.S. Missionaries Reported.”

On Jan. 21 came a big headline, top of page one: “SEIZE ALL WEST COAST JAPS, SOLON DEMANDS.”

“Jap” was a headline word. I’m not clear on how pejorative it was in 1942—it was different from today—but it was surely not helpful to the American Japanese that they and the enemy had the same name.

The “solon” in this story was Rep. Leland Ford, Republican of California. He was not a spokesman for the government, and maybe because he was speaking for himself his proposal was reported in unusually clear language.

Rep. Ford, the Times said, “advocated moving all Japanese, American-born and alien, to concentration camps.”

Rep. Ford said he believed there “may not be” any difference in the loyalty of those Japanese who were citizens and those who were not, and those who were loyal “should be willing to acquiesce in the movement of all Japanese people to whatever location the military authorities think they ought to be.”

In other words: Prove your loyalty by not complaining.

Below this big story was a tiny one: “Armed Jap Hiding at Pier Arrested.” A 17-year-old youth had been arrested on the Seattle waterfront hiding between two docks, “carrying an open knife.” How big a knife? What had he been doing? It did not say.

The paper offered no editorial comment on the trial balloon by Rep. Ford. The war rumbled on. On Jan. 21 came a story from the American forces trapped on Bataan: “Prisoners of Japs Bound and Stabbed.” On the same day: “Be on Alert for Coastal Sub Attack, Navy Warns.” There were also reminders during these weeks that Seattle was virtually undefended from air attack—though, as it turned out, it never was attacked.

On Jan. 25 was a story of two drunken Filipinos in Seattle who pull a knife on a Japanese American hotel clerk. The Filipinos were disarmed. “What started out to be a race riot turned into a near comedy,” the story said, the apparent comedy being the drunkenness.

On Jan. 28, some 500 employees of the Northern Pacific Railroad sat down on the job demanding dismissal of 12 “alien Japanese laborers.” The laborers were sent home. This sort of thing was not entirely new: earlier in the century there had been similar actions against Japanese and Chinese workers because they were willing to work for less than whites.

On Jan. 29, two Seattle Japanese were indicted for applying for an export permit, before the declaration of war, to sell gasoline tanks to China. The indictment said the tanks were really bound for Japan. The license was never issued and the tanks never shipped, but the government said the tanks were “capable of storing enough gasoline to enable 12,800 Nippon bombers to make round trips between Seattle and Tokyo.” No bomber could fly from Seattle to Tokyo and back, but it was a colorful way to illustrate the size of the tanks.

On Jan. 30 came a syndicated editorial column by non-Times employee Henry McLemore, which expressed in people’s English what many Americans felt. McLemore had just visited Los Angeles, and had been shocked by all the Japanese moving about, “free as birds.”

He wrote:

“There isn’t an airport in California that isn’t flanked by Japanese farms… They run their stores. They clerk in stores. They clip lawns. They are here, there and everywhere. You walk up and down the streets and you bump into Japanese on every block. They take the parking stations. They get ahead of you in the stamp line at the post office. They have their share of seats on the bus and streetcar lines.

“This doesn’t make sense. How many American workers do you suppose are free to roam and ramble in Tokyo? Didn’t the Japanese threaten to shoot on sight any white person who ventured out-of-doors in Manila? So why are we so beautifully courteous?

“I know this is the melting pot of the world and all men are created equal and there must be no such thing as race or creed hatred, but do these things go when a country is fighting for its life?

“Not in my book…

“I am for the immediate removal of every Japanese on the West Coast to a point deep in the interior. I don’t mean a nice part of the interior, either. Herd ’em up, pack ’em off and give ’em the inside room in the badlands…”

And that is what was done. But to go on:

“Sure, this would work an unjustified hardship on 80 percent to 90 percent of the California Japanese… (but) if making one million innocent Japanese uncomfortable would prevent one scheming Japanese from costing the life of one American boy, then let the million innocents suffer… Let us have no patience with the enemy or anyone whose veins carry his blood.

“Personally I hate the Japanese, and that goes for all of them.”

The Times never expressed sentiments like that. But it printed them. It says something that such sentiments were within acceptable bounds on a newspaper editorial page—and at many other papers, presumably, because it was a nationally syndicated column.

The Times did not have a regular letters page as it does today, but it made an exception and printed four letters from readers. One, a nasty anonymous letter, accused the paper of being “bought out” by pro-Japanese, because of its disgusting liberalism. One thanked the paper for McLemore’s column and asked for more. One complimented the paper for its toleration, and asked why it had printed that vitriol by McLemore. Finally, a state senator wrote that McLemore “screams in the best Nazi tradition regarding race and blood.”

The Times commented on Feb. 1, with a secondary editorial that raised the question of “what to do about resident Japanese.” It said, “the problem can and will be worked out by the proper authorities.”

On Feb. 4, the FBI began systematic searches of the homes of alien Japanese on Bainbridge Island, across Puget Sound, to confiscate firearms and cameras.

On Feb. 5 came a screamer headline, “8000 Jap Spies, Says Dies!” Rep. Martin Dies, Democrat of Texas, was head of the Committee on Un-American Activities, not a spokesman for the government.

In another anti-Japanese editorial column, McLemore blasted the “bow-legged sons and daughters of the Rising Sun” and the government’s pandering to them, which he found “mighty ridiculous.”

On Feb. 7 it was reported that 440 Japanese aliens had been interned in Seattle, and some of them shipped to Montana. On the editorial page, columnist McLemore discovered that 248 California Japanese-language schools that had been closed after Pearl Harbor were trying to reopen. His indignant response: “Slant my eyes, bow my legs and hammer me down.”

McLemore’s rant is remarkable not only in itself—“slant my eyes” was a slam also at the Chinese, who were our allies—but in the lack of any substantial article to counter it.

On Feb. 8, Japanese farms in California were raided by federal agents looking for cameras and guns. On Feb. 10, “Monterey Jap Colonies Raided” (California). On Feb. 12, “Japs Kill Filipinos, Toss Bodies in Bay” (Philippines).

On Feb. 13, page one, below the fold, came the big story again, this time more official: “Total Evacuation of Japanese on Coast Advocated.” “Total” was defined as “aliens and citizens alike.” The advocates were the entire congressional delegations of Washington, Oregon and California.

On Feb. 15, this idea was seconded by Thomas Clark, federal alien control coordinator for the Pacific Coast. Clark wasn’t saying whether Japanese Americans were dangerous, but that “if the Army and Navy say American-born Japanese are dangerous, I’ll take them out.”

On Feb. 16, at the top of page one: “Enemy Aliens Here to Be Ousted.” Aliens. And it said: “The government does not plan to intern” them, and that they can settle “any place they desire as long as it is outside the prohibited area.”

That was not true.

On Feb. 17, a little story appeared at the bottom of page one: “More Japanese Than Whites Study German at Broadway.” Broadway was a public high school in Seattle; as at other schools, the demand for German had fallen sharply since 1939. In 1942 of those studying German, 42 were white and 45 were Japanese.

From 60 years later, the response is, “So what?” The story did not spell that out.

On Feb. 18, columnist McLemore was at it again, strolling through San Francisco’s Japantown. “The Japanese were very nice to me,” he said. But he slammed them anyway by quoting the cab driver on the way out. The cab driver said that the Japanese had been shamed after Pearl Harbor, holding their heads down, but were “getting cocky again.” He said, “They ought chase ’em all to the hills.”

On Feb. 20, the Times reported “$100,000 Japanese Buddhist Temple Here Closed by U.S. Order.” The temple was closed by the Treasury Department for not having an alien-ownership permit.

On Feb. 21, Gov. Arthur B. Langlie, after consulting with military authorities, ordered all Japanese in the state of Washington, aliens and citizens, to give up their firearms within six days. Previous gun confiscations applied only to aliens in protected defense areas.

Did a state governor have such authority? The question of governmental authority was not raised—in this story or any story I read.

On Feb. 22, the FBI in Seattle arrested 103 Japanese said to be in an Axis spy ring. Big headline, few details.

On Feb. 25, 22 Japanese women, all U.S. citizens, resigned their jobs as clerks in Seattle’s elementary schools after a mothers’ petition called for their removal. “Mrs. Esther M. Sekor, chairman of the Gatewood mothers’ delegation, expressed approval of the action of the Japanese girls,” the paper reported. “‘I think it’s very white of those girls,’ said Mrs. Sekor. ‘They have our appreciation and thanks.’”

On Feb. 27, two Seattle Japanese were charged with being agents of Japan—for lobbying the state legislature from 1939 to 1941, when America was officially at peace with Japan, and for filming the Armistice Day parade in Seattle a month before Pearl Harbor.

On Sunday, March 1, came a long article on the local men testifying in Washington, D.C., before the Tolan Committee, headed by Rep. John Tolan, Democrat of California. This was a crucial story.

Gov. Langlie testified, favoring relocation of the Japanese.

D.K. MacDonald, president of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce, said Chamber members were of different minds on evacuation of the native-born Japanese, but did not like the uncertainty of not knowing. “We’d like to have a decision,” he said.

James Sakamoto, leader of the Japanese American Citizens League, offered to take custody of non-citizen Japanese (many of whom were elderly parents of U.S. citizens) and report weekly on them to authorities. “We want to be fighting shoulder to shoulder with other Americans, not hiding in some place of safety while others defend our homes,” he said. It was one of the few times any Japanese American was quoted.

Earl Milliken, mayor of Seattle, said, “The Japanese American Citizens League has been very helpful, but they won’t squeal on their own people. An Italian will come in and tell you if he knows of another Italian who is dangerous. The Japs keep such things down by coercion and threats, telling their subversive members they had better be good or else.”

He summed up: “Seattle residents overwhelmingly desire removal of Japanese—particularly aliens, but the feeling carries over to the native Japanese as well.”

On March 2, the state attorney general, Smith Troy, called for mass evacuation of “both alien and American-born” Japanese, to protect them from anti-Japanese rioting should a catastrophe happen overseas.

When asked about American-born Germans and Italians, Troy replied: “Speaking frankly, out here we feel we know the Germans and Italians a lot better than the Japanese.”

That was probably true. Ethnic Japanese were less a part of American society then. Most were farmers. Add to the physical distance between Japanese and most Americans the racial distance and the greater cultural distance. It is our tendency today to denounce our grandparents’ fears as “racism,” which amounts to condemning white Americans as wicked. That drops out the context of Pearl Harbor, the war (which was going badly), everything. Accept that much of their fear was understandable. Anyway, it was a fact. What should have been done about it? To control and civilize the response is why we have traditions, law, a Constitution and Bill of Rights.

On March 3 came the decision: “Army Order Reveals Eventual Ouster of All Coast Japanese.” The army did not say there had been an executive order by President Roosevelt. His name was not on it.

On March 4, the Times commented—still in a secondary editorial: “If the Army regards the complete evacuation as necessary from the military point of view, let it be done without undue debate and vituperation.”

It was done. The Japanese Americans were not fully evacuated until August 7, 1942, but decision was announced in March.

A few thoughts come to mind reviewing these reports, always remembering that this is one newspaper, probably one of the more liberal ones; and not even in the heartland of this dispute, which was California.

1. This was a different time. It was a war, with atrocities reported abroad and warnings about spies, saboteurs and invasion at home. In the March 7 paper was a page one map showing possible invasion routes on the West Coast, with a fat black arrow starting at the base of the Olympic Peninsula and striking toward Seattle and Portland. It was scary. All the stories about spies and saboteurs were scary, even if the details, if you thought about them, were faintly ridiculous: the man filming a parade or the boy by the pier with a knife. When it was announced March 8 that 20 Japanese aliens had been arrested in Seattle in possession of 120 swastika lapel pins—what could be deduced from that? Who in 1942 was going to wear swastika pins? Said the paper, “It was pointed out that the Japs possibly intended to use the swastika pins to identify themselves as fifth columnists in the event the Japanese army invaded Seattle.” All that seems ludicrous now. It probably didn’t, then.

2. Democratic politics were never suspended, even though the Constitution was. Internment was by executive order, but it was not without careful political testing. It started as a trial balloon floated first by a lone Congressman, then suggested by a group of Congressmen, then endorsed in hearings by local officials and called for by voices in the press.

3. Nobody fought the government. All the belligerency was on the pro-internment side. I did read a tiny story that the social workers opposed any mass internment on the basis of race. But there was no march, no picketing, no petition, no speech. Not even a letter to the editor. No columnist went to bat for the Japanese. Nobody brought up the Constitution and Bill of Rights. McLemore quoted the Declaration of Independence without naming it, only to kick it into the trash. Nobody else quoted it.

Remember the atmosphere after the one-day event of Sept. 11, 2001, and you’ll have an idea of the feeling during the continuing war in 1942. A faint idea. The American Japanese were keeping their heads down, following the Oriental maxim that he who puts up his head gets it cut off. None of the stories I read showed an ounce of belligerency from them.

On May 4, 1942, University of Washington student Gordon Hirabayashi intentionally violated the Seattle curfew on Japanese, and sued to demand his rights. That led the first of two infamous Supreme Court decisions on the internment, both of which the Japanese lost. But Hirabayashi’s very American act came too late to affect the decision for internment.

4. The language was unclear. Only once in three months of papers did I see the phrase, “concentration camps,” and it was early on, when the proposal was non-official. Men in authority had a common reluctance to name what they were doing. They did not call the proposal internment but relocation, removal or moving. Most of the stories did not concern themselves with where they were being moved; those that did, called the destination a colony or a center—never a camp, or, God forbid, a concentration camp.

And so it was done.

It enough people had stood up and named the act for what it was, they could have stopped it. But the statement is circular: how many would have been enough? The tide against civil liberties was strong, and I fear it would have taken a lot to halt it. I seem to remember that an editor of a small newspaper did campaign against internment, and was later praised, but it would have been much more difficult for a big-city newspaper with hundreds of employees and millions in advertising to do anything that smacked of giving aid and comfort to the enemy. It would have had a greater effect, but it would have been harder to do. Think, too, about that chamber of commerce president, the mayor, the governor, the members of Congress. They could have said no to the federal government, but it would have been exceedingly difficult.

After reading those papers, I have a better idea why the internment was done. It was not something to be proud of. And it is not something that gives me confidence in the protections of the Constitution at a time of psychological extremity. It is good that the words are there, but the words alone are not enough.

© 2002 Bruce Ramsey

After 2001, the issue came up again with Arab Americans. Perhaps the less-than-perfect comparison to Pearl Harbor reminded people of how the Japanese Americans had been singled out by race. This time, the country did a much better job of respecting the rights of minorities.