I had read of “regulatory capture” — industries that influence their regulators to such an extent that the regulators become their protectors. In the late 1990s, I was shown an example of just that: the household-goods moving industry in Washington. It had become a state-sanctioned cartel, and one man was defying it. He called himself Mike the Mover. I wrote several Seattle Post-Intelligencer columns about the movers, and, I think, helped to open up the industry to new competitors. And that was forgotten for 25 years, until a young journalist at National Public Radio put together a story about Mike the Mover. Here are the columns. [And here is the NPR story: https://www.npr.org/2023/06/14/1182214943/regulatory-capture-moving-seattle-washington-furniture]

In the 1990s I discovered that in the state of Washington, the home movers were operating under a regulatory set-up right out of the New Deal. Some of them were, anyway — and some weren’t. This is my P-I business column of Sept. 17, 1997.

Mike the Mover has been running for office every year, save one, since 1988. But his mark in history will not be for his name on the ballot. It will be for his guerrilla war on the state-regulated movers.

Mike is a marketing guy from headlight to hydraulic lift. Others have rolled quietly and illegally into household moving. Mike changed his name from Michael P. Shanks to Mike the Mover and put his picture in the Yellow Pages. In 1992 the regulated movers’ group, the Washington Movers’ Conference, complained, “Mike the Mover has made a mockery of our entire regulatory system.”

In Washington, Movers have been regulated since 1935. Jack Davis, attorney for the Movers’ Conference, says, “The concept was to protect consumers from the large power of carriers — to protect the public in respect to rates, schedules, loss and damage claims.”

What the law did, though, was to allow the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission to fix all the rates. No negotiation, no discounts. And Mike could not become a mover just by buying a truck. He had to convince the WUTC that the existing carriers were not adequately serving the market.

Mike tried several times. “Here’s how it works,” he says. “If you’re going to apply, you have to sign an affidavit promising not to operate while it’s pending.” The process takes a year.

At the hearing you face the other movers. Mike faced seven of them, and was turned down.

Mike had started in 1981 with one truck. When he painted his name on his trucks his competitors noticed him and complained. In 1987 the state cited him. In 1992 it hit him with a cease-and-desist order. In 1993 it slapped him with a court injunction to stop moving customers.

He ignored them all. WUTC enforcers wrote 89 tickets, each a gross misdemeanor, for operating without a license. Mike spent one day in jail. He continued in business.

Sharon Nelson, chairman of the WUTC, noted in a letter, “Part of the difficulty in building a case against him is the unwillingness of his customers to verify information.” Each month, Mike sent the WUTC a graph labeled, “Annual Sales Report – Born to Rumble.”

Mike rumbled into 1994, 1995 and 1996. In February 1996 he sued in vain to have the injunction lifted. The WUTC had lost its authority over him, he argued, “by completely abandoning and dismantling” its enforcement.

By this time, the Yellow Pages had many unlicensed movers. Some were “pack and loads” who stay legal by having the customer drive the truck, making the customer the “mover.” But others were lawbreakers providing full service, as Mike did.

In January 1997 state Reps. John Koster, R-Monroe, and Mike Sherstad, R-Bothell, filed House Bill 1455 to deregulate household movers. The bill died in committee. Mike’s business, with eight trucks and an annual volume of $1.2 million, rumbled on.

In June 1997 the WUTC took Mike to court for violating the 1993 injunction. It asked for $100,000 in fines, seven days in jail, seizure of Mike’s office equipment, disconnection of his phone and unplugging of his Web page, www.seattleweb.com/mike. On Sept. 5, Judge Robert Lasnik of King County Superior Court found Mike in contempt and set a penalty hearing for Oct. 15. There the matter is now.

Once again Mike is ordered to cease and desist, except for moves out of state or within Edmonds, Mountlake Terrace, Mercer Island, Auburn, Kent and Ellensburg. Mike’s lawyer, Greg Ursich, declares that Mike is in compliance. Under the pressure of the court, Mike has agreed to buy a household goods permit from another carrier for $35,000, subject to WUTC approval.

The WUTC’s deputy director, Paul Curl, says, “I think he’s making an effort. We recognize that.” Curl wonders, though, about a $746,483 claim against Mike by the Department of Labor and Industries. Mike says the claim was filed by a former employee as leverage in a fight over Mike’s trade name.

Curl also wonders whether a guerrilla warrior like Mike will really follow the WUTC rules.

A good question. Will Mike charge the regulated rate, $88.30 per hour, when he’s been charging only $75? Will he stop giving discounts to single moms and seniors? The better question is why such rules exist. What’s so special about the moving of furniture that requires a $35,000 permit and an adversary hearing to legally enter the business?

Curl allows that the entry restrictions are “a holdover from the old days.” WUTC staff, he says, is working on a proposal to loosen them up.

He adds, “The licensed carriers don’t want any change at all.”

Judge Lasnik ordered MIke to pay $5,000 in fines and $21,000 for the WUTC’s legal expenses. And 35 competitors objected to letting Mike buy into the industry for $35,000. Mike was defiant: “I am in business,” he insisted.

Mike the Mover was an ongoing story — and mine, too, because nobody else in the media was following it the way I was. Here is my P-I business column of Feb. 2, 1998.

Mike the Mover had been cited 89 times for moving houshold goods without a state license. He had been slapped with a court order and spent a day in jail. He had fought back, repeatedly running for public office, and had even changed his name from Michael Shanks to Mike Mover, middle name, “the.”

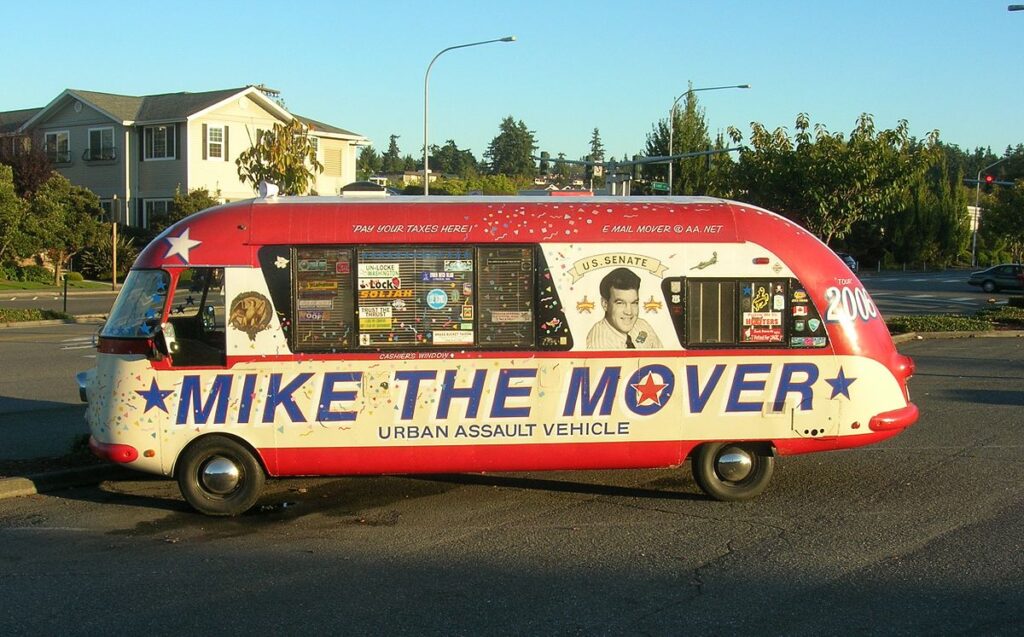

On Jan. 29, after nearly 17 years of guerrilla warfare, Mike arrived at the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission in Olympia in his political campaign bus labeled, “Urban Assault Vehicle.” Mike was in fine spirits. State government was about to officially admit his right to be a home mover.

Pat Dutton, the commission’s assistant director of operations, presided over the first-ever official gathering of legal and illegal movers. The commission, she said, wants to loosen its control over pricing and let new people into the industry. Controls ended years ago on trucking between states and cargo carriers and office movers in Washington. Only in household moving did the state pretend to set prices.

Unregulated movers had already run holes through that. Phone directories are full of movers without the required Interstate Commerce Commission or WUTC numbers. These are illegal carriers or pack-and-loads that skirt regulation by having the customer drive the truck. Directory companies don’t care about WUTC licenses, Dutton said. Customers don’t care, either, because they are saving money. Dutton cited a couple in Ballard that was quoted $2,100 by a licensed carrier and $600 by an illegal.

Why forbid such competition? State regulators would rather focus on consumer protection, she said. The WUTC would like to set up a mediation or arbitration system for disputes over such things as bills that wildly exceed estimates. It may want to make a rule on binding estimates. But as of July 22, much of the crate and entry control will probably go.

One idea is to let new movers into the industry for 180 days, inspect their consumer and safety record, and issue approved movers a license. This is revolutionary. New licenses haven’t been issued for years, and many of them date to the 1940s. Under the old system a would-be mover has to buy an existing license and fight for permission to operate it. (Mike tried and was rejected.)

To those on the outside, this seems unfair. “I’m a woman and a single mother,” said Michele Marsh, owner of Northwest Moving & Packing Inc. in Ballard. She has operated for the past five years without the WUTC’s blessing. “I think we all deserve the right to do what we do,” she said. “This is a free country. I don’t see why I can’t do this.”

Jack Davis, attorney for the Washington Movers Conference — the licensed movers — said he had been in the industry 36 years. “Transportation was regulated because it was ‘affected with the public interest’,” he said.

But the movers’ guild could not accommodate Mike the Mover, Michele Marsh or Bruce Palm, owner of Advanced Moving Services, a pack-and-load in Lacey. Palm said the market price for a license good for moves only within Olympia is $40,000. “It’s a little closed,” he said.

Several license holders spoke against free entry. Scott Creek, president of Crown Moving Co. Inc. of Seattle, said the Port Angeles market is large enough for only two movers. If someone moved in, he said, one of the two would have to get out.

“How would that hurt the public interest?” the WUTC’s Dutton asked.

“The individuals who were employed in that company would no longer be employed,” Creek said.

Mike spoke up: “That’s how it works in business, folks.”

Philip Elrod, president of Bluebird Moving & Storage of Vancouver, was a licensed mover willing to give up the old system. There are 40 movers in the Vancouver phone book, 18 of which have no Washington or Oregon authority, he said. His WUTC license, valued on his books at $40,000, “is worth nothing,” Elrod said. “I’m tired of it.” License everybody, he said, “and let them play by the same rules I play by.”

One mover warned that open competition would push down wages from $14 an hour to $8. “In California, there’s people who use pickup trucks,” said John Loidhamer of United Moving & Storage of Bremerton. “It ruins our industry because we can’t afford to hire quality people.”

“My guys all have a living wage,” Mike the Mover replied.

Davis noted that Mike was still in a regulated market. Could he have started up in a totally free market?

“You’ll never know,” Mike said.

David Spellman, an attorney with the Seattle firm Lane Powell, had a final thought. Everyone else has been deregulated. “How is this industry different from roofers, plumbers, lawyer and engineers?” he asked. “I’m a lawyer. We used to have fixed rates. We don’t anymore.”

He, too, had an investment in his career: $60,000 in law school tuition. Said Spellman, “I have no guarantee.”

Here is the story of an unlicensed mover who played the race card. It was my P-I business column of April 29, 1998.

The hearing hit a nerve when James Albertson played the race card.

The room at the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission in Olympia earlier this month was full of household movers, and they were almost all white. Albertson is black. According to notes taken by consultant Brian McCulloch, Albertson stood up and said, “I don’t see much diversity here among license holders.”

A man replied, “Don’t blame me that my grandfather got a permit.”

“That’s exactly the point,” Albertson said. “Your grandfather got one and mine didn’t. All I want is a chance to compete with you.”

For moving household goods across state lines, he can. But household moving has not been deregulated inside Washington. Officially, the industry has been a closed shop for 50 years. Unofficially it has been cracked open by unlicensed movers. Albertson, 52, bought control of Sprint Moving Inc. in Tukwila and has been in business two years.

Sprint and the other unlicensed movers have been so successful, and so useful to consumers, that the WUTC has said it intends to legalize them. In July it will open the door to the industry, breaking up the cartel of the past 50 years. As a first step, it has accepted Albertson’s $550 application for a new permit.

The licensed movers have been able to sell their heirloom permits for as much as $50,000, a value that is based on their ability to exclude competitors. That Albertson might get a new permit for $550 is bad news for them. He and his three vans have drawn an official protest signed by 28 companies, including Blue Ribbon Moving & Storage, Cascade Moving & Storage, Crown Moving, Evergreen Moving Systems, Lincoln Moving & Storage, North Coast Moving & Storage, Star Moving Systems, Tacoma Motor Freight Service, United Moving & Storage and Worldwide Movers. And it’s not just central Puget Sound companies that find him threatening. So do A.A. Star Transfer in Aberdeen and Eagle Transfer in Wenatchee.

Their protest says they and the other license holders “are ready, willing and able” to move any of th furniture that would be moved by Albertson, and that allowing him to do it would bring about “unnecessary and wasteful competition contrary to the public interest,” particularly in respect to “rates and charges,” and that he is not “properly fit, willing and able” to do business.

Not fit? “They don’t even know me,” Albertson fumes. “I do everything that any sensible business person does. I had $400,000 in sales last year. That means I’m doing something right.”

It may help prove he’s not “fit.” Jack Davis, the attorney for the 29 licensed movers, notes that operating without a permit “historically could establish a lack of fitness.”

Historically, yes. If you did not operate, you were probably not willing and able; if you operated without a permit, you were not fit. Under the new regime, this Catch-22 will be gone. The regulated rate now begins at $88.25 per hour for two movers and a truck, though unlicensed movers often discount it.

The licensed movers say rate cutting will cause companies to cut wages, cut service and use unsafe trucks. The WUTC does not agree. The state intends to regulate for consumer protection and safety, but to scrap the economic controls.

The question is now the details. Many licenses, for example, are good for some cities but not others. Seattle, Tacoma and Everett require a special endorsement, but Edmonds, Mercer Island and Kent do not. Full deregulation would mean these “commercial zones” would go, too.

Albertson is asking for full statewide authority. McCulloch, an insurance broker and consultant to the unlicensed movers, searched the WUTC’s records several years ago when he applied unsuccessfully for a license himself. The last mover to get statewide authority was a Yakima company — in 1948.

In 1949, McCulloch says, there were 208 licensed movers. Since then the state’s population has more than doubled, but the number of licensed movers was recently 207. Three are black.

Albertson says he doesn’t like having to remind the commission of that. “I don’t want it to be, ‘We had to let him in because he’s black.’ I want to be let in as a mover.”

Albertson is an entrepreneur. He started his first business selling hot dogs from a pushcart in downtown Spokane. He didn’t have to get permission from the other hot-dog vendors to do that, or inherit a license from his grandfather.

To his competitors, he says, “Who are you to say I can’t be a mover?”

Several progressives said they liked this column a lot. It was the race issue. I had highlighted “historic racism in the granting of moving permits,” wrote Sarah Luthens, an anti-WTO campaigner. Actually I never proved there was any racism, though probably there was. My thought was the same as James Albertson’s: he should be let in because anyone willing and able.

In Nov. 19, 1998, the Post-Intelligencer ran my final column on the movers.

On Monday, the state Utilities and Transportation Commission threw out the 1930s-era regulation of household movers and opened the industry to new entrants.

Mike the Mover wasn’t there. But the man who dared a decade ago to operate openly as an unlicensed mover, and spent more than $100,000 fighting the state’s enforcers, had spawned a whole industry of discount-price independent movers.

And if another label for them is illegal movers, as the licensed movers kept saying, it is a label that can be read two ways. “Anytime consumers are incented to seek illegal choices, something is wrong with the system,” said Anne Levinson, who chairs the utilities commission.

For decades, the system allowed the members of the Washington Movers Conference to block nearly every application for a new license. Originally issued for a nominal sum, licenses became worth $50,000 and more — evidence, said the utilities commission staff, “that the current entry process is not working, and that it needs to be opened up.”

Under the new rules, new entrants will be given 180 days, and then judged for safety and consumer complaints. As a test of the new rules, the commission has issued a license to James Albertson’s Spring Moving & Storage of Tukwila. Albertson argued in this column April 29 that the household moving industry had become a hereditary aristocracy.

Albertson is black, and the licensed movers are virtually all white males. To the state, licensing Albertson is the perfect statement of the new regime: no more private club.

The new rules also revolutionize pricing, which has already happened in the market. The old rules, widely ignored, fixed a rate of $85.05 for a truck and two movers. The new rules allow a maximum of 15 percent above that rate and a minimum of 35 percent below it. The utilities commission chose 35 percent because in moves of state employees, four out of five movers offered discounts of 25 to 30 percent.

The utilities commission staff didn’t want to set any minimum rate. It did it to mollify the Movers Conference, which raised the specter of predatory pricing.

Predatory pricing is when an established company sells below cost to drive out a weaker competitor, and recoups the loss by raising prices once the competitor is gone. It’s an odd argument: The licensed carriers are the established companies. In any case, if household moving is opened up, there is no way for anyone to maintain a monopoly price. Trucks are cheap, and they have wheels.

To set the new rates, the Movers Conference wanted a full-blown study, which is how the $85.05 rate was set in 1994. Speaking for the Conference, Lawrence Coniff argued that such a study would show costs have gone up and are “essentially the same” among competitors.

The state refused. Staff economist Tom McLean argued that opening the market will allow in people whose costs are different. The commission agreed to open the market now and measure costs a couple of years from now.

It also agreed not to regulate movers who pack the boxes but let the homeowner drive the trucks, or that drive the trucks but let the homeowner pack the boxes. These services didn’t exist when the regulations were written and have never been regulated.

The Movers Conference wanted them regulated. Well, they won nothing of consequence in Monday’s decision.

“The whole process has been a waste of my time,” said Doug Bernd, president of the Movers Conference and co-owner of Bernd Moving Systems of Spokane. Bernd said his company has been in the family for 60 years, and he had been hoping to pass it on to his children. The new system, he said, “is going to basically ruin an industry.”

Coniff said the reforms are radical changes (which they are), and they cannot be made without changing state law, which the Attorney General’s office disputes. The Conference may file a lawsuit.

Shoreline insurance broker Brian McCulloch spoke for the Association of Independent Movers of Washington, which one opponent called “a self-styled non-existent organization of illegal movers.” McCulloch agreed that partial deregulation is all the state can do under the law. “We’re still in favor of complete deregulation,” he said. “In January, we intend to go to the Legislature.”

The next question will be whether his members, some of whom have been doing fine without licenses, will bother to apply for them.

In June 2023, National Public Radio did a story about how Mike the Mover had opened up the moving industry in Washington. NPR called me and they called Mike, and quoted both of us. And they got the story right.

The Legislature never did fully deregulate the home movers, but the new system was much more pro-consumer. The UTC offered Mike a license, but he told me it wasn’t for full authority, and he turned it down. He operated for another 20 years, and retired when his doctor told him he was no longer up to moving furniture. He shut the business down rather than sell it.

“There’s only one Mike the Mover,” he told me.