When Princess Diana Spencer of the United Kingdom died in a car crash in Paris on Aug. 31, 1997, I was an editorial writer at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. I was appalled by all the sentimental weeping in the American media over a foreign princess who, in my jaundiced view, had not been a person of importance. My old P-I colleague John Snell, who was working at the Portland Oregonian, wrote me: “I’m sitting here now hearing the woman three desks away, who used to write the ‘relationship’ column, argue that men just can’t understand the tragedy of Princess Di’s death. And I thought if there ever were deaf ears for an appeal like that to fall upon, they’re the ones hanging on the sides of YOUR head. Of, course, I could be wrong.” He wasn’t wrong; fresh on the editorial page and bursting with opinion, I wrote this column at home on Sept. 17. My editor said it was too late to run it, and it never ran.

Tradition instructs us not to speak bluntly of the dead. But Diana Spencer has had such fanciful praise heaped upon her, including a cover story in Newsweek and endless hours on television, that some sort of balance has to be struck.

Diana was a celebrity. She was not a Marie Curie, an Amelia Earhart or a Margaret Sanger. She invented nothing, pioneered nothing and changed nothing of any substance. She was responsible for no great undertaking. When a sober and serious history of the 20th century is written, Diana Spencer will not be in it.

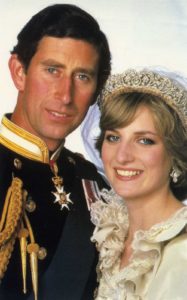

She was a beautiful princess, embodying the fantasies of those who grew up with Golden Books and Walt Disney tales. She bore the aloofness and adultery of her Prince Charming in a princess-like way, and only stepped out on her own later on. She suffered much, vomiting her meals and throwing herself down stairs. By talking about her problems, she made herself more like ordinary folks, which won their hearts. She was beloved, but she was no Joan of Arc or Aung San Suu Kyi.

Diana Spencer was a caring person. She campaigned against land mines. If that alone makes her heroic, then Hollywood movie stars are heroic for similar pronouncements. Diana was no authority on land mines. She did not devote her time to removing them or working with their survivors.

Such people do exist. Diana met those people, toured their working places, made speeches and went away. Hers was a celebrity’s commitment. Such commitment is more commendable than signing a contract with Weight Watchers, as her fellow princess Fergie did, and it is proper that Diana is remembered for it. But it is not a life’s work.

In earlier centuries, royalty did have a life’s work. Hers, as Princess of Wales, was to bear the United Kingdom two sons and to be a good mother to them. This she did well enough. One wonders how she would have fulfilled her obligations had she married the Egyptian and gone off to live with him.

Her death leaves the United Kingdom with her ex-husband, Prince Charles. He is a figure much less sympathetic, a professional grandee. He will continue to sniff flowers and play polo while his mother, the queen, lives on. One is tempted to say Charles will not make a good king, but how would we know? At the dawn of the 21st century, what does a good king do?

We Americans decided back in 1776 to owe allegiance to no crown, and to maintain no tribe of royals at public expense. It was the right decision. Here you earn respect by what you do. As longtime friends of the British, we should pay our respects when their princess dies. But as Americans, we should keep our sympathies within republican bounds.

I sent Snell a copy of this column and he replied, “I’m not so sure I’d give her credit for being a good mom. Good mothers don’t leave the youngsters at home while they take off to Paris to party with a rich gigolo. Do we really think the driver was the only person in that car who was falling-down drunk? You’re the gigolo, you’re stone cold sober and you turn to the only person so drunk he probably can’t even walk without bumping into stuff, and say, ‘You drive.’ The whole story sure puzzled the hell out of me.”

© Bruce Ramsey 1997