Nope, not this one.

I wrote this account of the Seattle newspaper strike of 2000-2001 shortly after it happened. I published it in the classical liberal and libertarian journal Liberty, May 2001. Nobody at work ever mentioned it; I assumed they hadn’t seen it. I didn’t name my employer in the piece, but I didn’t do anything else to conceal it. It is, of course, the Seattle Times. The first newspaper I mention, the one where I was a member of the union, is the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

Whether workers should be forced to join unions is a question that, at least to the readers of this magazine, is settled. But what to think of an actual union, whether voluntary or otherwise, is a different question, which becomes urgent when the union calls a strike.

By 2000, I had been a member of the Newspaper Guild for 16 of the previous 21 years. I had had no choice in the matter if I wanted to write for that newspaper. I didn’t believe in compulsory unionism, but after some years I had become active in the union to work for a better pension. I was in it, and I figured I might make use of it. It was a frustrating experience, especially after I concluded that the company had no intention of being helpful and the union had little clout. I also realized that the workers could have had a much better pension and 401(k) plan if we had voted out the union and accepted the package our nonunion colleagues already had.

Early in 2000 I accepted an offer at the city’s other daily. My new employer had a modified closed shop, requiring nine out of every ten new hires to join the union. I asked to be a “one-in-ten” and was hired with that status. This saved me union dues of 1.5% of gross pay and, I thought, the necessity of ever having to worry about the union again.

It was not to be so. In November 2000, nine months after I got the job, the union struck both papers. It was the first strike for either paper since 1953.

The first question was: Do I strike? As a one-in-ten, I was not in the union. But legally I was represented by the union and covered by the contract. Unlike the management employees, I would be protected by federal law if I walked out. I could also join the union, though if I did, I could not go back to being a one-in-ten.

Two days before the strike a senior reporter came to my office and suggested that I join the union. I wasn’t sure whether the visit was official or not.

“I don’t think I need the union,” I said.

“You probably don’t,” he said. “But other people here do. The guys on the loading dock. We need to stick together. Your colleagues are in it, and it would be better if you joined it.”

Was that a threat? No.

I declined.

A few days before the strike, the company began circulating paperwork. I had a right to strike, it said, there could be no reprisals, but it was a serious act. I would not be paid, and after the first of the month, I would get no medical benefits. And the company wanted to know in writing whether I intended to strike.

The head of the family that owned the newspaper came to my work group. He is a man of deep sentiment — particularly about his family’s commitment to the paper. The union was not being reasonable, he said. Their demand was money, and they were asking for larger percentage increases than anybody in the industry was giving out, and more than it was reasonable for him to pay. The union had had a rally in the little park across the street from his office — his little park, owned by the company — carrying signs denouncing his “profits” and “greed.” The signs were offensive. His family had not been greedy about taking money out of the business. Just the opposite. They had accepted a rate of return about one-third of the corporate chains’, in order to serve the community. They did this mainly by hiring extra employees.

Did the employees appreciate that? Apparently not. Some of the union signs called the company a “plantation.” His family compared to slave owners! Some of those people carrying signs weren’t even his employees.

But we were. He paid our wages. Wouldn’t we be loyal to him?

It wasn’t a matter of loyalty to him, one of us said. Yes, some of the things on the protesters’ signs were ridiculous. We don’t think this is a plantation. We’re not against the family. But it isn’t that simple.

The four others in my work group all went out on strike.

That was the first notable thing. None of my colleagues needed the union. Their membership had been compulsory. Yet they were members, and when the union said to strike, they struck. None expected me to join them, or even urged me to. And I didn’t urge them to join me.

We did what our status implied.

The company took on the look of a fort. Hurricane fences, bolted to the sidewalk, went around the entrances, and around the little private park across the street. The union made a fuss about those fences, especially the fence around the park, and how un-familylike it was. The company also boarded up the lunchroom windows, so the picketers on the sidewalk couldn’t peer inside.

When I got to my desk that first day, I found that my computer and voice-mail passwords had been erased, along with everyone else who was union-affiliated. I had to get new ones. The union complained that all their company cell phones stopped working, portraying it as a petulant act.

I already had a new ID badge, blue instead of white. My badge had to be visible for me to get into the building. There were lots of new security guards, too, big muscular guys, most of them black. The union made a fuss about how threatening they looked, though they were unfailingly polite. Sometimes they would videotape the picketers, and the union would complain about that, too.

The security company replaced our cafeteria caterer. The new food wasn’t so good, but it was free. It was all you could eat, four meals a day plus snacks. All the machines were on free vend. Pull a lever, and Boom! Diet Pepsi. Doritos. M&Ms. All you wanted. There was a freezer full of Dove bars.

On the first night, the managers were issued folding cots, and slept next to their desks. I went home. The next day I took the bus in, which I almost never do, and met colleagues at an assigned place for a strikebreakers’ van. The van came, and I met a couple of young employees from other departments. They were one-in-tens, too.

Comrades.

At the company, the pickets blocked the van. The driver said, “Hang on.” Just before two minutes were up, the pickets counted down, “Four, three, two, one,” and parted. We got through, and entered the building through the basement, next to the big rolls of newsprint and more security guards.

About the third day of using the van I saw a manager walk up the sidewalk and cross right through the line. From then, I walked through the line. I didn’t need the van. It was a polite strike. There was no violence, no threats, and hardly any nasty language. The worst that I ever heard was the word, “scab,” which some people seemed to think deeply hurtful.

I had a dictionary called The Lexicon of Labor, written by one of the union men out on the picket line. I looked up the word, “scab,” to see if I was one. Yep, I was. But it was a word from another time. Most of my contacts with strikers were simply greeting friends. A couple of times I gave a striker a hug. She sent me a Christmas card with a playful reminder that I was on the wrong side.

John L. Lewis would have been disgusted.

In framing the strike around money, the union said that pay hadn’t kept up with inflation. The company said that it had. The two sides seemed to define “pay” differently, the company counting more things than the union did. I spent no time trying to verify these claims. The only thing I knew about pay was that I was satisfied with my own. Having accepted the publisher’s offer in free negotiation nine months before, it seemed faintly ridiculous for me to hold up a sign saying, “UNFAIR.”

The strikers had a lot of public sympathy — not because the public understood the issues, but because they were strikers. Seattle has a history of unionism. When the strike began, our Democratic mayor announced that the city departments would not speak to us. We claimed in our editorial columns that this violated the First Amendment (which was not true) and that Hizzoner was taking sides in a private dispute (which was). The mayor backed down. The governor, a Democrat of more practical stripe, never boycotted us, though he would not visit the paper as long as there was a picket line around it.

In a newspaper strike, the key for the company is to get the paper out. We got it out. It was thin that first day, with only two sections, but it looked like a paper, and it was free. All the coin boxes were modified to dispense the paper for free. Several weeks into the strike, when the paper was back up to about four sections, we put it up to 25 cents, which was half-price. It was a sign that the company was winning. A few days later the vending machines for the strikebreakers went from free vend to 25 cents. That was another sign.

One of the interesting things was the solidarity among the managers. They took pride in showing that one manager could do the work of several union members. Lots of them had been members of the union at one time or another. One had been president of the union. He was the one who walked through the line in front of my van.

When your identity changes, your loyalty changes.

There was similar camraderie in the union. I was told of strikers who started unsure, saying in meetings that the company had been good to them, but a few weeks later repeating the union’s grievances. Strikers wrote testimonials afterward. “The solidarity has been great,” said one. “I was going to support my co-workers no matter what.” Another said, “People are feeling free, euphoric. Our sprits soar. We are empowered.”

One striker told a reporter, “I feel good about myself, having stood up for something once,” though she allowed that the union’s issues were not her own. It was a common attitude, and to me, an odd one. If it’s not your issue, why stand up for it? I had more understanding of the person who really did think the company was unfair, like the page-layout man who wrote in a piece at the strike’s end, “I sat out there in the cold and the rain, huddled around a rusting burn barrel and began to feel oddly exhilarated. Here I was, losing large chunks of money that I’ll probably never recover (certainly not with the money proffered in this stingy contract) and I was positively giddy. How could this be?

“Maybe it’s simply this. We get few opportunities in this life to stand up for ourselves. We’re constantly asked to toe the line, to ‘get along.’ I’ve been a master of the ‘get along’ for so long, I almost forgot what a backbone feels like. It feels damn fine, thank you.”

On the inside it felt oddly exhilarating, too. It was also an act of defiance to cross the picket line, and to have one’s name and photograph on a column in the paper being struck.

The people who took it hardest were those who were unsure or who changed their minds — most obviously, the strikers who decided to “cross.” For some, that decision came when it became obvious that the strike was a lost cause. For others, it was when the union called for a subscription boycott, which was spitting in the punchbowl we all drank from.

Some of the reporters got together and had meetings at a private home. Some were saying to the union leadership: Let us vote on the contract offer or else we’ll cross. They had not been allowed to vote on it. They had voted earlier to give the union negotiators a strike authorization, which left the decision to call a strike up to the leaders. Now they argued about the offer, and could not reach a decision as a group. For one thing, the union negotiator was there, arguing that it would be wrong for any union member to cross. Most of them didn’t.

Crossing alone was difficult. One colleague talked at length with her boss, made arrangements to cross, and changed her mind. This was after the company said there would be layoffs after the strike was settled, but that strikebreakers would keep their jobs. My colleague realized that if she reclaimed her job, she would bump a striker in her work group — and she was in a work group of five. It was too much like pushing someone out of a lifeboat. She found a job in the next state at a nonunion paper.

A features columnist crossed, late in the strike, and wrote her first column about it. “Every conversation I’ve had about this strike could have easily have been about religion,” she wrote. “Friends spoke of growing up in a ‘union family’ with the same reverential, say-no-more as ‘Catholic family’ or ‘Jewish family.’ I would not dare judge them. We shared childhood strike stories about parents who were policemen or garment workers and, like my mother, teachers. We nodded at the need to stand together.

“But this was a stand visited on me, not one I chose… It’s as if a stranger came to my door, invoked the name of a beloved, deceased relative, and demanded that I follow.” She decided she couldn’t follow “when I could no longer see where we were going.”

That columnist was birdshot with hostile e-mails. One of the “alternative” weeklies sneered at her “sappy” column. The other “alternative” weekly (both of them are nonunion) mocked her for several weeks, repeatedly running her picture. This paper had run a column during the strike called “Scab Watch.” I had never been included in Scab Watch, or harassed in any way—because, I suppose, I was not a member of the union.

What you’re supposed to think depends on who you are.

This columnist had enunciated a principle — that one should always be responsible for where one is going. But “principle” was mainly a word used by the union. A strike leader wrote at the strike’s end, “Walking off your job, leaving friends and maybe your career behind in the name of principle, is a disturbing leap of faith. It’s a headlong rush into a tunnel with no other side, the solitary pursuit of a nebulous goal that every single atom on the planet except certain portions of your heart and gut insists is a suicide mission. It is all consuming, sleep depriving. Maddening. In other words: Lord, it was wonderful.”

What principle?

Another columnist wrote, “I don’t cross picket lines.” That was his principle.

Is that a good principle? If the leader of the strike calls it “a headlong rush into a tunnel with no other side” — a fair description — does principle require you to follow?

In an industrial battle, with millions of dollars being expended like artillery shells, what does it mean when those who called the strike over money say afterward that it was not about money after all, but about “respect?” The union went out for money and didn’t get it. All the negotiations at the end were over the terms of the union’s surrender.

Here was the outcome. Management, who had known in theory that the paper was overstaffed, saw unmistakably that this was so. At the same time, they had a financial hole to fill. They announced that of 800 union-represented jobs, 160 would go away. This would be done by partly by voluntary buyouts. Also the strikers would be called back over six months, some of them to jobs other than what they had.

The reporter who had urged me to join the union never returned. He took a job with a California newspaper.

I kept my job. If I’d joined the union and gone out on strike, I’d have been the last in my work group to be called back and the first on the eventual layoff list. That’s not why I had crossed the line; on that first day, none of us was making that sort of calculation. The strike was a step into the dark. The strikers went out with a belief that they were protected by the contract, by the National Labor Relations Act or by something. In the sense that mattered, they were not.

All this goes beyond the political idea I started with, which is that unions should be voluntary, that they should gain the right to represent workers one at a time, in respect of the freedom of association. Unions in the United States do not believe in the freedom of association. Under the National Labor Relations Act, passed during the New Deal, union representation is created by majority vote. The Newspaper Guild at my employer held that vote in the 1930s. They never held such a vote again. They didn’t have to. That vote, taken at least a decade before I was born, subjects me to a union contract in the year 2001 even though for all I know, all the people who voted may now be dead.

What a joke.

The strike left me with a harder attitude about collective bargaining. You cannot bargain collectively unless you are willing to think and act collectively. That means letting other people decide whether you strike, and how long you strike, and under what conditions you come back to work. Those are big decisions. They could cost you your job. They cost several of my friends their jobs — friends who trusted those decisions to the union.

They are the sort of decisions I want to make for myself.

I am not a union man.

© 2001 Bruce Ramsey

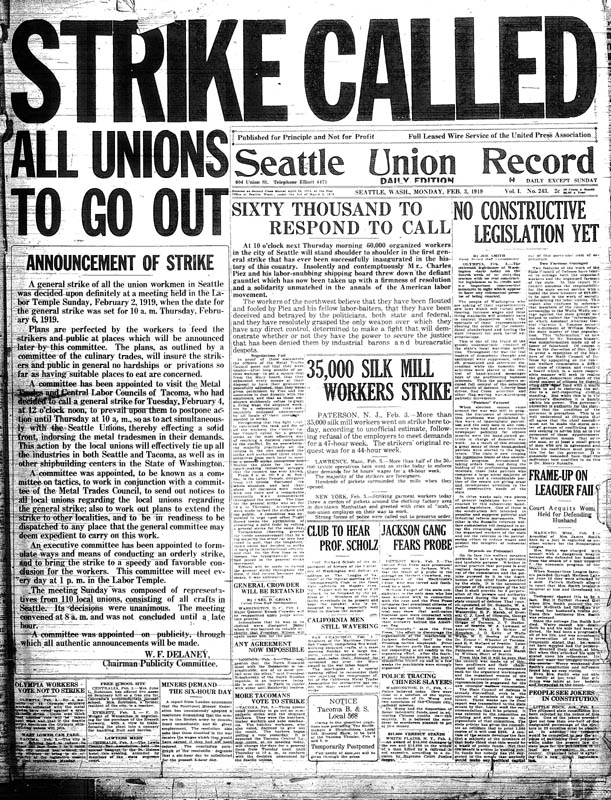

Years after I wrote this I dug into the history of the 1930s in Seattle. I found that the Post-Intelligencer had recognized the Newspaper Guild as the result of a strike, and that there was no representation vote. A mere 35 members of the Guild won union representation for all the reporters and photographers for the next 70 years because Dave Beck’s Teamsters beat the crap out of any employee who dared to cross the picket line. So much for democracy and the National Labor Relations Act.