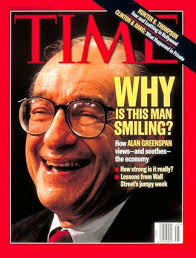

The ‘Maestro’

Alan Greenspan was a former acolyte of Ayn Rand who became the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Radical libertarians called Greenspan a sellout, but I didn’t think he was. I liked him. My review of his book appeared in the December 2007 Liberty, but was written in September, just before the decade’s high in the stock market, and one year before the crash on Wall Street.

One might distinguish among the various chemistries of libertarians by their reaction to Alan Greenspan and his new memoir, The Age of Turbulence (Penguin, 2007). Greenspan has long been the most prominent libertarian inside the executive branch of the U.S. government. Indeed, he has been lodged in it so long, and has, until now, addressed the public in such gnarled syntax, that a good number of his fans had given up on him. But if they had followed him closely, they would have seen that his views had not materially changed. In the book, he calls himself a libertarian Republican.

More than fifty years ago, Greenspan, then a young economic analyst with his own consulting business, joined Ayn Rand’s inner circle. In The Age of Turbulence, he credits Rand with opening his mind to non-career-related questions. Before Rand, his thinking had been “empirical and numbers-based, never values-oriented.” He was a logical positivist, and recalls proclaiming to Rand that there were no moral absolutes. She pinned him with those big eyes and asked him whether maybe he didn’t exist.

He said he couldn’t be sure.

“Who is making that statement?”

Greenspan was unlike the others in her circle in that he was more aloof, older than they, and the only one who had achieved something in the world of business. Rand respected that and cut him some slack. “She allowed him more intellectual liberty than she did other people,” Edith Efron once said. Rand never disowned Greenspan, as she did Efron and Nathaniel and Barbara Branden. And he was loyal. When she cast out the Brandens and asked her circle to sign a statement siding with her, Greenspan signed it.

By then, 1968, he had joined Richard Nixon’s campaign for president, having been recruited by another Rand fan, economist Martin Anderson. Rand endorsed Nixon, too. A few years later Nixon would impose wage and price controls and cut the dollar’s last tie to gold. He is not remembered fondly by libertarians. But in 1968, a year of war, riot and assassination, the alternative was Hubert Humphrey, the heir to Lyndon Johnson. Nixon was the one.

Greenspan was offered a job in the Nixon administration, and he turned it down. In his book he says he could not tolerate Nixon’s psychology. Of Tricky Dick, he wrote: “He hated everybody.” But Greenspan kept his Republican contacts, and in 1974 he was named chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers by President Ford. Greenspan was sworn in with Rand standing next to him. Later, after she died, he was named chairman of the Federal Reserve Board by presidents Reagan, Bush I, Clinton and Bush II, serving 18 years in the top economic position in the U.S. government.

Some will excommunicate him for being a central banker, and say he sold out. One article on the radical libertarian web page LewRockwell.com was fancifully called “Is Alan Greenspan a Malignant Alien Life Form?” But whether he had sold out would depend on what his purpose was. Should every libertarian make the spreading of libertarian ideas his life’s work?

In his book Greenspan says he did not accept all of Rand’s ideas. (One wonders: Did he say that to her?) The point of disagreement was her declaration that taxation is theft, and therefore wrong. He writes in his new book, “If taxation was wrong, how could you reliably finance the essential functions of government?” Others had asked that question; in her newsletter she had proposed a system of voluntary funding, though it was not convincing. Upon reaching this question, many of her followers became anarchists. Others decided that anarchism and capitalism contradicted each other, and agreed with Greenspan that capitalism requires “state-enforced property rights.”

Breaking with Rand, even over this one point, was liberating to Greenspan:

I still found the broader philosophy of unfettered market competition compelling, as I do to this day, but I reluctantly began to realize that if there were qualifications to my intellectual edifice, I couldn’t argue that others should readily accept it. By the time I joined Richard Nixon’s campaign for the presidency in 1968, I had long since decided to engage in efforts to advance free-market capitalism as an insider, rather than as a critical pamphleteer.

For Greenspan, economics was not only a belief but also a business. The part with market value — at least, the market Greenspan served — had to be constructed by induction and based on facts.

There is a story early in the book. In 1957, Greenspan analyzed the purchases, use and inventory of steel by the major American steel-using industries. One of the producers, Republic Steel, was his client. Greenspan flew to Pittsburgh and told the CEO that Republic’s customers were not using all the steel they were buying, because their business was soft. Orders for steel were bound to fall, and Republic would be smart to anticipate that. The CEO wasn’t inclined to take the advice of this geeky young analyst from New York. Steel orders were good, and he kept his lines going. Shortly afterward, orders stopped and the economy slid into the 1958 recession. At the next meeting the CEO allowed that Greenspan had been right.

Greenspan could look into the chaos of numbers and see order. That was his skill. In doing so, he developed a picture of the economy more detailed than the pamphleteers’. They are interested in explaining the market as an idea essentially the same in all times and places, and there is an aspect in which that is true. But actual markets change, and not only in their level of freedom, but also in their complexity, depth and resilience. What the market can do at one time is different from what it can do at another.

The defenders of the capitalist idea may not be interested in that, but actual capitalists are. For example, consider steel. When Greenspan visited Republic, Americans weren’t importing steel. They could have, but they weren’t. Shortly afterward there was a strike, and they did. In the years since, the U.S. output of steel from iron ore has shriveled, replaced by steel from recycling mills and producers abroad. There are consequences of this — to someone thinking of investing in the steel industry, or working for it, or buying its products or dealing with it politically.

Consider Greenspan’s later field, money. As Greenspan acknowledges in the book, inflation is endemic to fiat-money systems. If your point is that commodity-backed money is better than fiat money, well, fine, but it is a point of theory. In the past 70 years the reality has been only fiat money — and some brands of fiat money are better than others. Central bankers make the difference. Some of them print money parsimoniously, and their currencies have been the stronger ones. Facing an inflation, some have been willing to slam on the brakes, and some unwilling. Paul Volcker, Greenspan’s predecessor at the Fed, restored much of the integrity to the dollar by running the U.S. economy into a wall.

Greenspan didn’t have to do that. During his time, the dollar was just as much fiat money as before, but monetary roughness wasn’t needed — and Greenspan implies that it wasn’t all because of what Volcker had done. Something in the global environment had changed that affected all currencies in the developed countries. “Even a slight ‘tap on the brake’ induced long-term rates to decline,” Greenspan writes. “It seemed too easy.”

In 1987 the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds was 10.8 percent. It fell for 16 years. In 2004, when the Fed began pushing overnight rates up, Greenspan expected the 10-year yield to finally rise, because that’s what it would normally do. But it didn’t.

The cause of the reduced pressure, he argues, was the fall of communism and the movement of millions of Chinese, Eastern Europeans and then Indians into the global market. “Wages and prices are being suppressed by a massive shift of low-cost labor,” he says in the book. When the bulk of these workers are absorbed, he says, the pressures on prices and wages in America and Europe will return. In the next few years, he says, we will feel “a return to fiat-money normalcy.”

For radical libertarians, the objection to Greenspan is his pragmatism. But he would not have had the job he did, and the influence he had, if he had done things their way.

That doesn’t mean he always subordinated himself. In the Bush II administration, Greenspan’s soulmate was the first Treasury secretary, Paul O’Neill, the former CEO of Alcoa Aluminum, who Bush later fired for political disloyalty. Greenspan portrays Bush as intensely partisan, and, unlike Clinton, unwilling to bend his program to fit economic reality. Greenspan has praise for Clinton and his Treasury man, Robert Rubin, who brought the federal budget back to surplus. Bush had no financial discipline, and during Greenspan’s time vetoed not one spending bill. Under Bush, he writes, “I certainly did not qualify as part of the inner circle, nor did I want to be.”

Greenspan says in 1987 he accepted the job as chairman of the Fed vowing to follow the law, though he was “an outlier in my libertarian opposition to most regulation.” He says, “I planned to be largely passive in such matters and allow other Federal Reserve governors to take the lead.” He found, to his surprise, that the Fed staffers were more market-oriented than he had thought. They were cautious about substituting their judgment for the market’s, and were willing to review old regulations and toss them.

Greenspan does portray himself as wielding some power. The Fed sets overnight interest rates on loans among banks, and he talks briefly about that, and is a lender of last resort in a crisis, and he talks briefly about that. He argues that the lender of last resort has to be the government, because the private sector cannot do it “without impairing a bank shareholder’s value.” He notes that the bailout of Mexico was a loan, not a gift, and that it had a high interest rate, and that the Mexicans paid it back early. He noted also that the other big bailout, of an investment group called Long Term Capital Management, was with private capital, with the Fed acting as a broker.

The Fed chairman’s No. 1 job is to keep the rate of inflation down, and under Greenspan it came down substantially, but it was mostly not his doing. Greenspan’s No. 2 job was to prevent catastrophic downturns. After the crash of October 19, 1987, he opened the money spigot and there was no downturn, and after the burst of the dot-com bubble in 2000 he did the same, and there was a downturn that was not catastrophic. But any Fed chairman would have done the same.

What is more interesting is his response to the two booms: the dot-com ecstasy under Clinton and the Bush II housing speculation. After famously warning in December 1996 against “irrational exuberance” — a thought that came to him while soaking in the bathtub — Greenspan was laughed at. He looked more deeply at the data of productivity, he says, and saw real and striking improvement. Maybe the gigglers were right, and the exuberance was grounded in fact. He decided that some of it was and some of it wasn’t, and you couldn’t tell one from the other until it was over. So Greenspan let the boom run for another three years, raising interest rates only modestly, and letting the dot-com bubble pop on its own. And under Bush II, Greenspan did not cut off the housing boom. Part of it was a political motive: when people own housing they are friendlier to capitalism, and Greenspan appreciated that.

From his book, it seems that behind the syntactical smoke, Greenspan was thinking clearly and acting with motive. He believed in economic hands-off, and that is where he mostly kept his.

He was not able to reinstate the gold standard, which was ended in 1933 by an act of Congress and could not be revived by Fed fiat. Though he expresses a “nostalgia” for an anchored currency, he says, “There is no support for a gold standard today, and I see no likelihood of its return.” But “monetary policy can simulate the gold standard’s stable prices,” he says, and he tried to do that. The result was not a dollar as good as gold, but it was better than it had been.

On the currency issue, he concludes, “There is no inherent anchor in a fiat-money regime. What constitutes its ‘normal’ inflation is a function solely of a country’s culture and history…” If America does not have the culture libertarians envision, in the past half-century has gone toward it in the realm of economics. In the early 1970s a Republican president imposed price controls and Democrats called for an “incomes policy.” We do not hear these things today. That the federal government runs the economy, and the president is personally responsible for the rate of unemployment is an idea that survives, but at far less amplitude. That is a change, and Greenspan played a role in it by running the Fed the way he did. Bob Woodward called him a maestro, but that was for show. Really he was more of a Coolidge.

Greenspan has written a thick book, much of it filled with his economic view of the world: thoughts about China, India and Russia, about the fall of communism, about corporate scandals in America, the cost of entitlements, and so on. For readers who have kept up with these topics, much of what he says will confirm what they already know. Unlike his Congressional testimony it is well written. And there are some notable thoughts, among which are these:

@ The U.S. presidency attracts people who are not psychologically normal. Greenspan worked for Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush I, Clinton and Bush II. “I came to see that people who are on top of the political heap are really different,” he writes, and not different in a good way. The most psychologically normal among them was the one not elected: Gerald Ford.

@ Three times — on pages 256, 371 and 431 — he says regulators cannot guarantee the honesty of banking. Fraud and embezzlement is exposed by whistle-blowers, not bank examiners.

@ Antitrust doesn’t work.

@ Hedge funds move too quickly to be regulated by the government. In general, he says, “Markets have become too complex for effective human intervention.”

@ Bank-deposit insurance does create a moral hazard, but on balance it is worth keeping.

@ The widening gap between the pay of the average worker and the highly skilled undercuts public support for capitalism. One fix: open the doors to immigration of the highly skilled.

@ Some CEOs are paid too much, and ought to have their pay cut — not by government, but by stockholders.

@ Outside directors on corporate boards generally don’t know the business. For large public companies, CEO autocracy is “probably the only way to run an enterprise successfully.”

@ Medicare’s long-term problem will be fixed “by rescinding the benefits of the more affluent.”

@ In making peace with the federal budget deficit, the Republicans “swapped principle for power” and in 2006 “deserved to lose.”

@ The lack of motivation by state oil companies to increase production is hastening the day when other energy sources — tar sands, shale, gas hydrates, nuclear and coal — begin replacing liquid petroleum.

@ Governments’ determination to fight global warming by cutting CO2 emissions is mostly talk. People will support cap-and-trade schemes only when the cap is set too high to do any good. “Remediation is far more likely than prevention.”

@ “The Iraq war was largely about oil.”

The last comment got some media attention, and it is the one he explains the least. Really he does not explain it at all. There is almost nothing in the book about foreign policy — but then, Greenspan was an economics guy. Always remember that.

© 2007 Bruce Ramsey

Greenspan’s reputation as “the maestro” was about to shatter. If I had written this for Liberty a year later, I would have had to deal with the Austrians’ argument that Greenspan had caused the panic of 2008 by pushing down interest rates and ignoring a speculative bubble. The Left accused him of wrecking the economy because he opposed more regulation. Both camps essentially argued that he could have stopped the boom had he stepped in and poured cold water on it.