In December 1978, I became the new marine writer at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. I wanted to cover the total eclipse of the sun coming on Feb. 26, 1979, but the eclipse wasn’t a waterfront story. The paper sent a much more senior guy to cover it, so I took a day off and went as a tourist, taking pictures. (The one above is mine.) Mark Funk, the Everett Herald’s reporter, had snagged an invitation from Goldendale’s mayor to stay at his house the night before. The mayor and his wife were hospitable folks, but as good Christians, they were to share our enthusiasm for the Druid rites we witnessed at the Stonehenge memorial.

The Seattle Times’ eclipse coverage gave prominent attention to the Druids, but the P-I’s didn’t, as I recall it, because their reporter had been at an observatory instead of the Stonehenge. I wrote a short version of the Druid ceremony for the P-I’s editorial page, which didn’t print it, and a longer one for a private newsletter, “Notes from the Underground,” edited by my friend Mike Dunn. This is based on the longer version.

I do not believe in magic—not even after the solar eclipse of 1979. But I confess that a few more performances like the Druid rites at Maryhill and I’ll begin to ponder the ancient texts.

I went there with Mark Funk, a reporter for the Everett Herald.Maryhill, Washington, is on a spot overlooking the Columbia Gorge, and was to be right in the eclipse’s path of totality. It was supposed to have the clearest viewing in the Pacific Northwest. Maryhill also has a curious monument, a concrete Stonehenge built a few years after the total eclipse of 1918. The concentric rings of stones officially commemorate the men of Klickitat County who fell in World War I. But the Druids, it was said, believed the monument was really built to prepare for the celestial event of February 26, 1979.

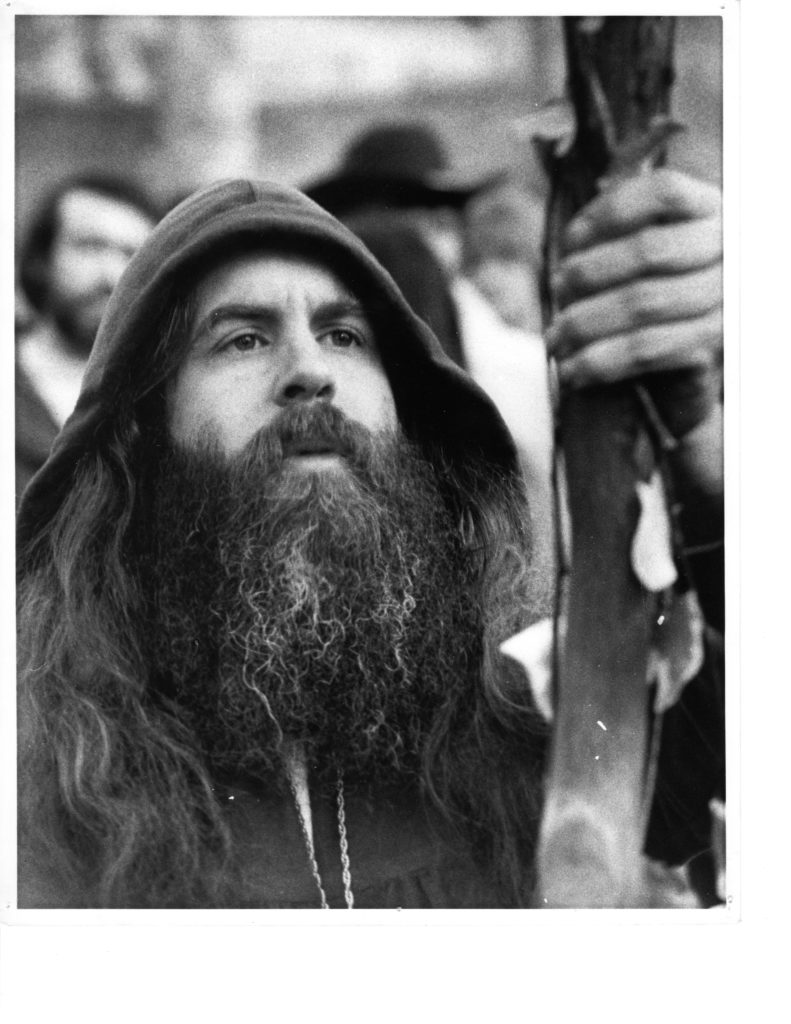

Funk and I had heard about these Druids, and set off the night before to find some. There among the gawkers with their Toyotas, Volkswagen buses and REI tents walked a bearded man in a white robe and necklace. He told us he was with the New Reformed Druids of Oakland, California. He was one of about 25; others had come from Berkeley and Redwood City, and locally, from Longview and Olympia. I pegged him as a guy with a limp handshake.

He was walking with a woman. “Everybody!” she said, not very loud and to nobody in particular, “Let’s get together some collective energies and do something about this weather.” It was soggy and cool with an overcast sky—an ill omen for the next morning’s event.

Ten minutes later, she had us linking hands under the dark clouds. A candle flickered and threatened to go out, casting an eerie light on the stones. The inner ring, about eight feet high, had somebody sitting on each stone, witnesses to our participation.

“Ommmmm,” somebody intoned, and everybody went “Ommmmm.”

Silence.

Then again: “Oooooommmmmmmm.”

People raised their handclasped arms and held them until they tingled. Silence. It was embarrassing. The group needed a leader.

The Druid man started a children’s folk song about flowers and trees. None of us knew it. Then a woman said, “Hey, it’s your birthday, Michelle.” With nervous relief, the folks with the Toyotas and Volkswagens all sang, “Happy Birthday to You.”

Somebody picked up the refrain from the Beatles’ “Hey Jude,” and the collective energies began to rise. “Na, na-na, na-na-na-na, na-na-na-na, Hey Jude,” soon changed to, “Sun, sun sun, su-u-u-un, su-u-u-un, sun sun,” though the sun had gone down hours before.

Lit by two candles, Stonehenge looked like an old MGM set. As the chant droned on, the Druids approached the altar stone and reverently laid down a sword, a goblet and a leather boot. People sang “Amazing Grace.”

One star poked through the clouds right overhead.

A cheer! A gray-cloaked Druid grabbed the boot and yelled:

Goddess is alive! Magick is afoot!

Goddess is alive! Magick is afoot!2

Everyone joined in. Another star winked on, and a few more glowed through a veil. The chant gave way to a rhythmic clap, clap, clap-clap-clap. A few women broke from the circle in free-form dance.

Clap, clap, clap-clap-clap.

The veil tore open and revealed a sparkling band of sky. People broke into a melee of dog-howls and cheers.

Mark and I drove back to Goldendale, satisfied. We were staying at the house of the mayor, Cy Forry. Mark had interviewed him over the phone, and wangled an invitation. Forry, a meat salesman, was married to a woman who took her Bible seriously.

Mark described the Druid chants and parting of the clouds with enthusiasm. “Pretty powerful magic,” he said.

“No, that’s not so,” insisted the mayor’s wife. “They don’t have any magic. Put this magic out of your head.”

I changed the subject; I didn’t want to give her the satisfaction of agreeing with her. Nor could I defend the Druids’ yeasty brew of nature worship and feminism. These people wore the clothing of prehistoric Celts. They spoke of cleansing and redeeming the planet. Their leaders were Earth Mother-type women, and they worshipped “the feminine within all of us.”

February 26, 1979, promised to be their day—if the sun would come out. The weather reports said there was a 70 percent chance of clear sky, but you had to be an optimist to believe it. At first light it was cool and damp, with a thin layer of clouds.

The long grade down to the Columbia was creeping with campers and cars. Across the river, in

the shadow of cliffs, the headlamps of big trucks on Interstate 80N3 streamed through the last swath of night.

We headed for Stonehenge along with crowds of the curious. There at the center of the stones a woman with long black hair and a green robe began: “I am Morning Glory Zell of the Church of All Worlds.”

Four Druids faced outward. To the north, a woman held up a headless Cro-Magnon figurine of exaggerated hips, belly and breasts. To the east, a black-robed man presented a broadsword, point downward. To the south, a man held a deer skull on a forked stick. To the west, toward Morning Glory Zell and the altar, a young woman offered a brass cup. The four intoned a litany, and the woman sipped from the cup.

The sun was half gone, but it was still obscured, and the clear sky to the west looked impossibly far away.

Morning Glory Zell lifted her arms skyward and began:

Magickal mirror of darkness,

Golden creator of light,

Your embrace for the moment surrounds us.

In shadow we search for insight.

From the flesh of the planet we grew.

She is our mother; let her be healed.

People and trees, dolphins and bees,

We are the children of the earth.

Let the earth be healed.

Your embrace for the moment surrounds us.

In shadow we search for insight.

From the flesh of the planet we grew.

She is our mother; let her be healed.

People and trees, dolphins and bees,

We are the children of the earth.

Let the earth be healed.

The sun was three-quarters gone, but still behind the veil. Unless it broke out, we would not see the corona at totality.

The Druids took up a chant:

The prophesies will come when shadow mates with sun.

The prophesies will come when shadow mates with sun.

The chant died. The sun was a crescent, nearer to the clouds’ edge.

Next to speak was Isaac Bonewits, a curly-haired fellow in a white robe and eyeglasses, representing the New Reformed Druids of North America: “Now,” he said, “for the most powerful chant known to man:”

Rain, rain, go away! Come again another day!

Everyone joined in, some yelling “rain,” some yelling “clouds,” and some just yelling.

The sun slid out into the clear.

The blinding crescent began dissolving from both ends, shrinking to a star on the lunar disk, like an unearthly diamond ring. Thousands held their breaths, and the point of light winked out. An eerie darkness fell. People shivered.

For two and a half minutes, we dropped our mylar viewers and stared directly at the black disk framed by the shimmering corona. It was as if the moon were a clay plug on a furnace of molten steel, with the edges popping silently with white-hot power.

Too soon, one of the edges began to glow brighter than the other. The diamond ring winked on, and the sparkling stone spread outward into a crescent. The eclipse was over.

Mark and I had stood in just about the only place in the state of Washington with an uninterrupted view. At the Goldendale Observatory, 15 miles away, the scientists, amateur astronomers and reporters who had bought $30 press passes saw the spectacle from behind the clouds.

Rational observers, including myself, may put it all down to good luck for us, bad luck for them. But then, they had no Druids beseeching Mother Earth.

No scientists publicly commented on this, but the Christians couldn’t let it pass. Minutes after totality, as folks were streaming back to their Toyotas and Volkswagens to create the biggest traffic jam in the history of Maryhill, along came a sound truck, booming:

Do not worship cre-a-tion; worship the Cre-a-tor. This e-clipse is brought to you by Je-sus.

It was the Druids’ day.

“Now I know why the Druids lost out,” was the reaction of the P-I’s editorial page editor. He said the piece was “twice as long as it should be,” and rejected it. It would be 15 years before I had a column on the P-I’s editorial page.