The following story ran on Post Alley September 4, 2023. It is based on a section in Seattle in the Great Depression and some research on 1918.

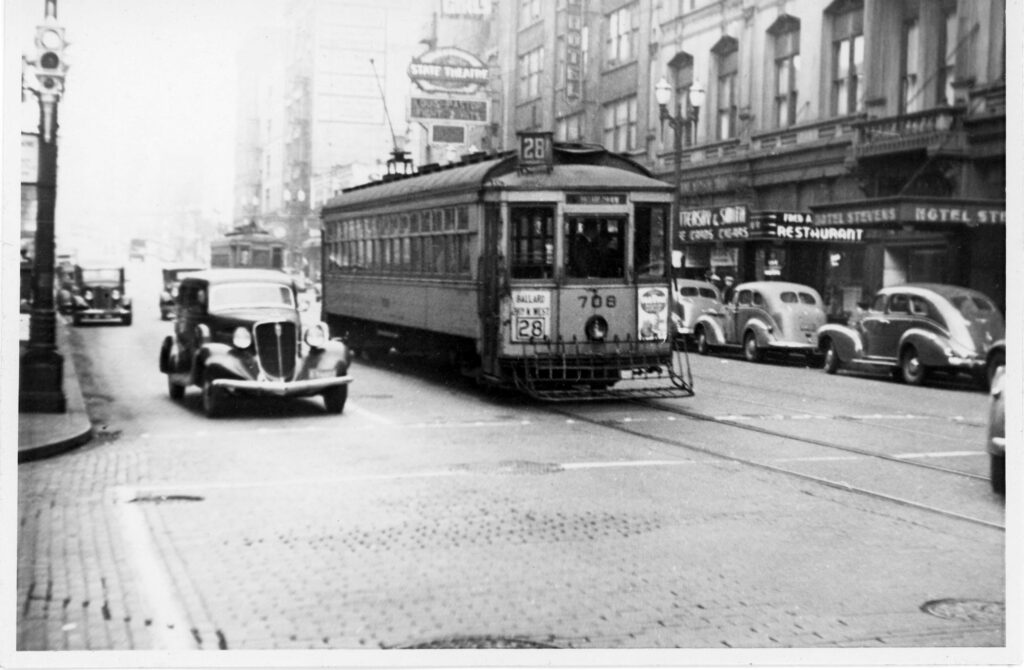

In the 1930s, streetcars were the principal means of public transit in Seattle. The city had more than 230 miles of tracks. People rode to work on the streetcars, rode to school on them, and rode them downtown to the city’s great department stores. Yet, early in the 1940s, before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the city ripped out the tracks and replaced the streetcars with buses.

For years, I’ve heard people express their regret over that decision. Seattle people love streetcars — at least, the idea of them. In recent times, they’ve allowed their leaders to spend millions of dollars on two short streetcar lines that hardly go anywhere and aren’t connected. Now the city has a plan to spend millions more to connect them in a line that still won’t amount to much. Yet the city once had a system that had lines to West Seattle and the Rainier Valley, to the U District and Ballard, and a web of lines covering Queen Anne, Capitol Hill, and the Central District.

Here and there, you can see where the lines ran. A street will seem unusually wide, such as Greenlake Avenue North south of Woodland Park, or will have a median strip, such as 8th Avenue Northwest in Ballard. Those ghosts were once streetcar lines.

Was it a mistake to scrap them? A look at the history suggests that it was a good decision, and one that hardly could have been avoided.

The first electric streetcars in Seattle came in the late 1880s. They were privately owned and operated for profit. In the days before automobiles, public transit was operated by private enterprise, without public subsidy. In November 1918, Seattle voters approved by a 3-to-1 vote the $15-million deal. In 1919, the city took over the lines and handed over the bonds. In 1920, the city raised fares from a nickel to three rides for a quarter. And in 1921, revenues for the system were the highest they would ever be again.

In the 1920s, Seattle’s streetcar revenues were sucked up by the bondholders and the workers. There was no money or new streetcars, or much for maintenance, either. As Seattle people bought automobiles, streetcar ridership fell by one-third. In 1931 the Argus, a longtime Seattle weekly, wrote, “If anybody predicted fifteen years ago that the time would come when we would have miles and miles of rusty rails and rotten ties, sunken at the joints; that the service would be as rotten as the equipment; that the system would be plunging deeper into debt every day, that we would become so used to it that we would hardly criticize it, he would have looked at them with scorn. Yet that is what has happened.”

By 1929, the city had met its bond payments for 10 years, and had paid down the sum owed Puget from $15 million to $8.3 million. The streetcar boss, George Avery, said paying the rest from farebox revenue was not possible. He asked for a 2½-mill property tax.

Supporting public transit with taxes was a new idea, and established opinion was against it. The problem of the streetcar system, the Seattle Times said, was that it had been run by politicians; the answer was to put it in the hands of a businessman who knew how to make a profit. In the Depression year 1932, the city council handed over management of the city streetcar lines to Walter M. Brown, the president and principal stockholder of the city’s last remaining private line, the Seattle & Rainier Valley Railway, which ran to Renton. The Rainier Valley line was not much of a money-maker. It had defaulted on its bonds and was in terrible shape. But Brown was a businessman.

Brown wanted to impose pay cuts on the city workers, but he wasn’t allowed to do that. On some lines he cut out every other stop, so that the cars would move faster. His reforms saved money, but the public hated them — and at the next election they threw out the mayor, Robert Harlin. The new mayor-elect, John Dore, promised to fire Brown on his first day in office. Brown got the message and went back to his private streetcar line.

Dore kept most of his reforms, which did help. Still, for the next five years, Seattle’s municipal streetcar system was in constant crisis. Service was bad. The Depression was on, and property owners were in no mood to raise property taxes. All around the country, streetcars were dying. In Seattle, Walter Brown’s Rainier Valley line ran its last car on January 1, 1937. The city took over the tracks and cars, sold them for scrap and replaced them with buses.

Puget brought in a consultant from New York, and a plan was devised for the city system. The Seattle Municipal Street Railway would borrow $12 million ($255 million in today’s money) from Wall Street, pay off the remaining debt to Puget at 56 cents on the dollar, and buy a whole new system. It would not include streetcars; the new cars cost too much and weighed too much. To use modern streetcars, Seattle’s 200 miles of remaining track, much of it on wooden ties dating to the 1890s, would have to be replaced with new track laid in pavement. The New Deal had been willing to fund Grand Coulee Dam and would help fund the Mercer Island floating bridge — but not this. That meant for Seattle, it would be buses or nothing. The buses could be electric trolleys, but they would have rubber tires. No tracks.

In March 1937, this new deal was put to the people. Mayor Dore, who had no alternative plan, denounced the deal the council had made. In a debate with Councilman Arthur Langlie, who supported the deal, Dore called it a “wicked swindle” by Puget Power that was “so crooked it smells to high heaven.” Dore’s populism worked. Voters recalled the swindle of 1918 and voted 58 percent no.

A year later, when Dore was dead and Langlie was mayor, the plan came up again. The loan, which was from the federal government, was a bit less, and Puget’s share, 36 cents on the dollar, was less, but the plan was essentially the same. The streetcars would be replaced by buses, and 200 miles of tracks ripped out. The people of Seattle were not asked to vote on it. City officials just did it.

Were they wrong? Buses were what the city could afford. They were also safer, because buses come to the curb. Streetcars ran down the middle of the street, so that passengers getting on and off had to cross automobile traffic, and when the streetcar turned a corner, it had to cross automobile traffic, too. Every year, people were injured or killed in streetcar accidents.

Still, Seattle people loved their streetcars. Their votes suggest that most of them wanted nice, new ones, with no increase in taxes. And that was not possible. Langlie gave voters the system they needed, and they accepted it. It was not a bad decision. Probably it was the only decision. No other plan was seriously offered.

© 2023 Bruce Ramsey