In 2006, I went with my family to East Asia. I have always managed to get columns out of my foreign vacations, and this was no exception. On this trip I had an insight about urban rail transit. My Seattle Times column ran on July 26, 2006.

Several years ago, I received an e-mail from an official of Sound Transit, the agency building light rail in Seattle. The official was touring in Europe, and had been riding on a subway in Munich. He loved the experience. Why, he wondered, couldn’t the shortsighted Seattle critics of rail transit see how good it was?

I have heard these sentiments many times, and having recently ridden the subways of Seoul, Beijing and Hong Kong, I see what he meant.

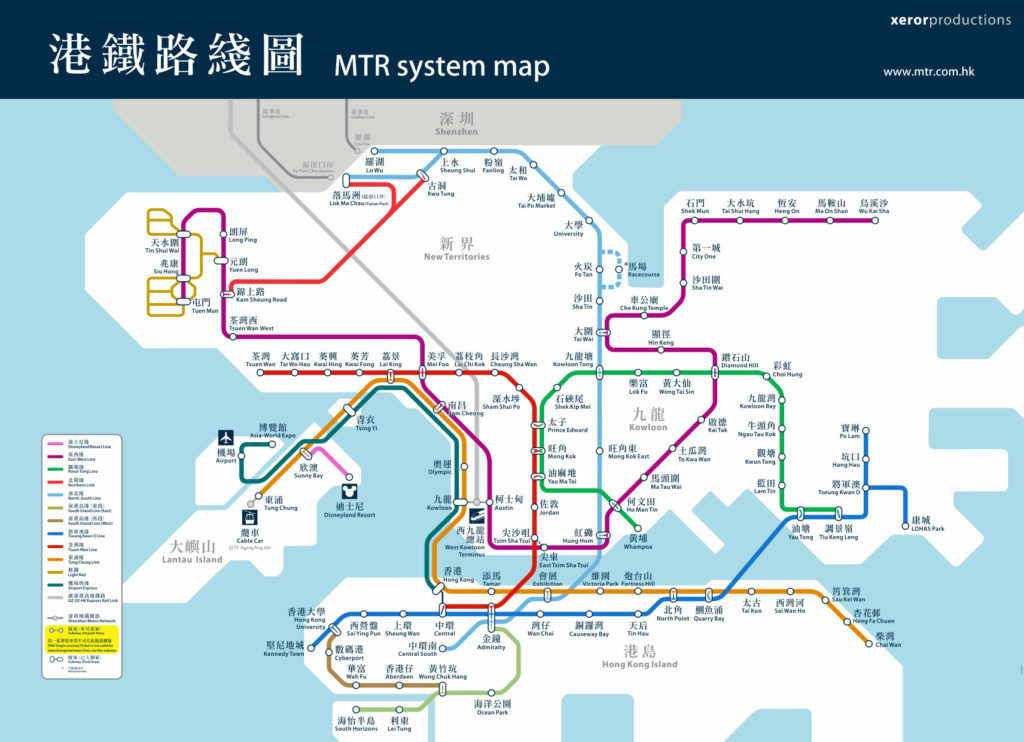

The rail systems in those cities were radically more useful to me than buses. The maps sold to tourists always showed the entire subway system, each line a different color, with a dot for each station and a name, both in the local alphabet and in Roman letters. The subway map was posted in the stations and in each railcar.

This simple map let me plan my trip without asking any non-English-speaking person a question. I always knew where I was, because each station was announced by a taped message — “Next station, Tiananmen West” — and labeled with big signs: “Tiananmen West.”

None of the cities did this with their bus systems. I saw no map of bus lines. The front of the bus might list its final destination — usually someplace I’d never heard of — but I had no idea of the route. If I knew that, I would still not know where I was on it. Bus stops were not labeled, so there was always the question: “Is this where I get off?”

In Hong Kong, the people at my hotel said to catch the No. 7 bus on the Waterloo Road and get off at the Holiday Inn. Suddenly, the bus was no longer a mystery machine. It was just as reliable as rail and in this case more convenient. But the bus system had to be learned one line at a time. The subway system could be comprehended as a whole.

The subway also made ticketing easier. There was a ticket window and sometimes a row of ticket machines that were easy to learn. On a bus, you’re expected to have the exact change with no fumbling, and maybe talk to the driver in his own language.

Finally, rail was convenient because it tended to go to the places tourists wanted.

I could see why a tourist would leave Seoul, Beijing and Hong Kong believing rail superior to buses. For my purposes, rail was superior. But then again, I didn’t live there.

A city transit system is mainly for locals. They will be less interested in simplicity and more interested in how many different places the system can take them. A resident has time to learn the bus system, which can go many more places than a train.

Also, the resident’s choices are different. A foreign tourist will be comparing a subway to a taxi, or walking — and will think the subway gives him a lot of new options. The resident will already have the use of a bus, maybe a bicycle, and likely a car. To the resident, the subway adds less.

Nor does the tourist worry about the tax costs of rail transit. Someone else pays them. In all these ways — needs, knowledge, alternatives and cost — the resident is unlike the tourist. The tourist’s enthusiasm is not relevant to him, and really he should ignore it.

There is another matter: The cities I visited — Seoul, Beijing and Hong Kong — are much denser than Seattle. Hong Kong has 6.9 million people, Seoul has 10.4 million and Beijing has 14 million. Each of these cities has huge areas of high-rise apartments, which are needed to make high-capacity transit work. Seattle is mostly single-family houses — a low-density city whose most useful vehicle is — dare one say it? — the private car.

Anyway, light rail — a kind of subway system — is coming. I expect Seattle people will be disappointed in its usefulness to them personally, but they may be proud of it. And the tourists from Montana will all be able to understand it.

© 2006 The Seattle Times

This was another argument that fell into a well. By 2006 people had made up their minds about it.