A few times as a columnist I simply wrote about a memory of youth — in this case, the summer of 1967. Here is a column written for the dull days when the air was too hot to focus on serious topics. It ran in the Seattle Times on August 23, 2006.

In the lazy end of August, I escape to a teenage memory. It was a long summer in the 1960s. I was 15, and had a bookish fantasy of living off the land. Maybe I had absorbed it from “Huckleberry Finn” or “Lord of the Flies” or one of the Jack London stories about freezing in Alaska. I lived in Edmonds, a half-made piece of suburbia on the shores of Puget Sound. The Indians had lived off the Sound. If they could do it, we could do it for three days.

I called it the Survival, and marketed it to three friends. They didn’t live by the Sound, but I would show them how.

We made our camp in a sandy gully by the tracks of the Great Northern. It would mean boxcars rumbling by, some of them occupied by hoboes, but it was by the Sound and a high bluff shielded us from the eyes of responsible adults.

That first afternoon, we cast for fish from the granite sea wall. After much effort, we caught two flounders, which I filleted inexpertly with my pocket knife. The plan was to grill them over hot coals, but our fire took an unreasonable time to burn down. We placed our fillets in the flames and seared them to the griddle. My attempt to pry off the first one flipped it into the sand, ruining it. The second I extracted, but one side was black and the other like Jell-O. On the edge were two bites of properly cooked fish, taunting me with what might have been, with proper management.

For the rest of the evening we bottled our hunger with canteen water and illicit cigarettes, at least until midnight, when we set about raiding people’s gardens. This was cheating, of course, but it was a Survival, and we had to eat. I set the rules of theft. This was my neighborhood, and there would be no wrecking stuff. We would steal only what we could consume.

The first place we hit was Bingham’s. A few years earlier, Bingham had planted an apple tree, and it bore one fruit. All the goodness in that young tree had gone into one glorious Red Gravenstein. I had eyed it for a week. One day I dashed across his big yard, captured the prize, took it off to a hiding place and consumed it down to the pips. It was the finest apple I have ever eaten, but I paid for it — to my conscience, though not to Bingham.

This time, we taxed him of some plums, a fruit for which our desires were limited by known side effects. Then it was on to Nivens’, who were family friends. There we collared some carrots, which we wiped on our pants and ate, grit and all. We also nabbed four ears of corn. Dad had taught me how to cook corn, camp style: you soak the ears in water for an hour and grill them with husks on. However, it was 1:30 a.m. and our fire had gone out. We ate our corn raw.

The next morning, we smoked some more cigarettes and went digging for food in the tide flats of Browns Bay. Butter clams were small, and trouble to dig in the rocks and gravel where they lived. Mussels, we mistakenly believed, were not edible. We dug horse clams, which piled up fast. I didn’t know what to do with horse clams, so we took turns lugging the bucket up to my house.

My parents were leaving for Seattle. “You should have gotten butter clams,” my mother said. “You have to clean these. I use them for chowder, though I guess you could roast them over your fire. Of course, if you want to give up your Survival, there is plenty of food in the house.”

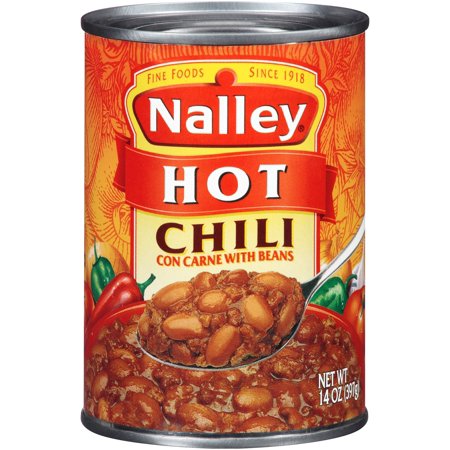

They drove off. The four of us, having faced Nature for less than 24 hours, had to choose between a bucket of horse clams and four cans of Nalley’s Hot Chili, with soft beans, curls of ground beef and delicious gobs of orange fat.

Our Survival was over. I never suggested one again.

Later, I would meet folks who had fantasies about living off Nature for long and grubby periods. I figured they didn’t know what they were getting into — or maybe they did, and were just different.

© The Seattle Times

Patricia Davis, Port of Seattle commissioner, wrote, “My father had an apple orchard outside of Wenatchee, and that, like all types of farming, was WORK… When I went off to college and the hippies raved on about getting back to nature, I was highly amused. I told them to go try, like you actually did. Everyone should have the experience.”